The Low Status

Moat Matters

High performers need to cross it to build agency

Why do high performers find it increasingly hard to perform even better? Because the difference between good and great is the willingness to repeatedly cross the valley where competence drops, and status disappears. This valley is an invisible moat which most high performers are not willing to cross because it calls for travelling through an uncharted territory. An overabundance of status protection, triggered by an evolutionary neurological mechanism, prevents them from taking unnecessary risks. Converging research from neurobiology, behavioural economics, and network science suggests that the only thing preventing a leap across this biological moat is ego, not ability.

This is how I am crossing my moat.

I'm a founder. I've raised capital, built companies, and survived an acquisition. But everyMonday morning, my stomach drops, because I have been trying to cross a different moat. Writing. This very newsletter.

I've pitched VCs, managed crises, and made payroll when the bank account was empty. None of that made my hands sweat the way hitting "publish" on a piece of writing does. Because when I write, I'm not in my domain of mastery anymore. I'm a novice. A founder trying to become a writer. A similar story was narrated by a friend, a technology leader who's built AI systems at scale. He's terrified to post on LinkedIn. "I can talk about this stuff in my sleep," he told me. "But posting a thought on AI? I rewrite it seventeen times and never publish. What will people think?"

When you're world-class at one thing, your brain over-indexes on protecting your existing reputation capital. Think of reputation as a portfolio. When you consider learning something new, your brain runs a calculation: "If I try this and am bad at it, I'm not just failing at the new thing but devaluing my entire portfolio. " This calculation is rational. Protect your assets. Don't take unnecessary risks.

By hitting the publish button, I am taking an unnecessary risk. But, what I've learned - and what every founder who's made multiple leaps has learned - is that greatness requires repeatedly crossing something I call the Low Status Moat.

The geography of growth

When you move from one domain of mastery to a new one, you inevitably enter an uncharted valley where your competence, efficiency and status are no good at survival.

This is the Low Status Moat.

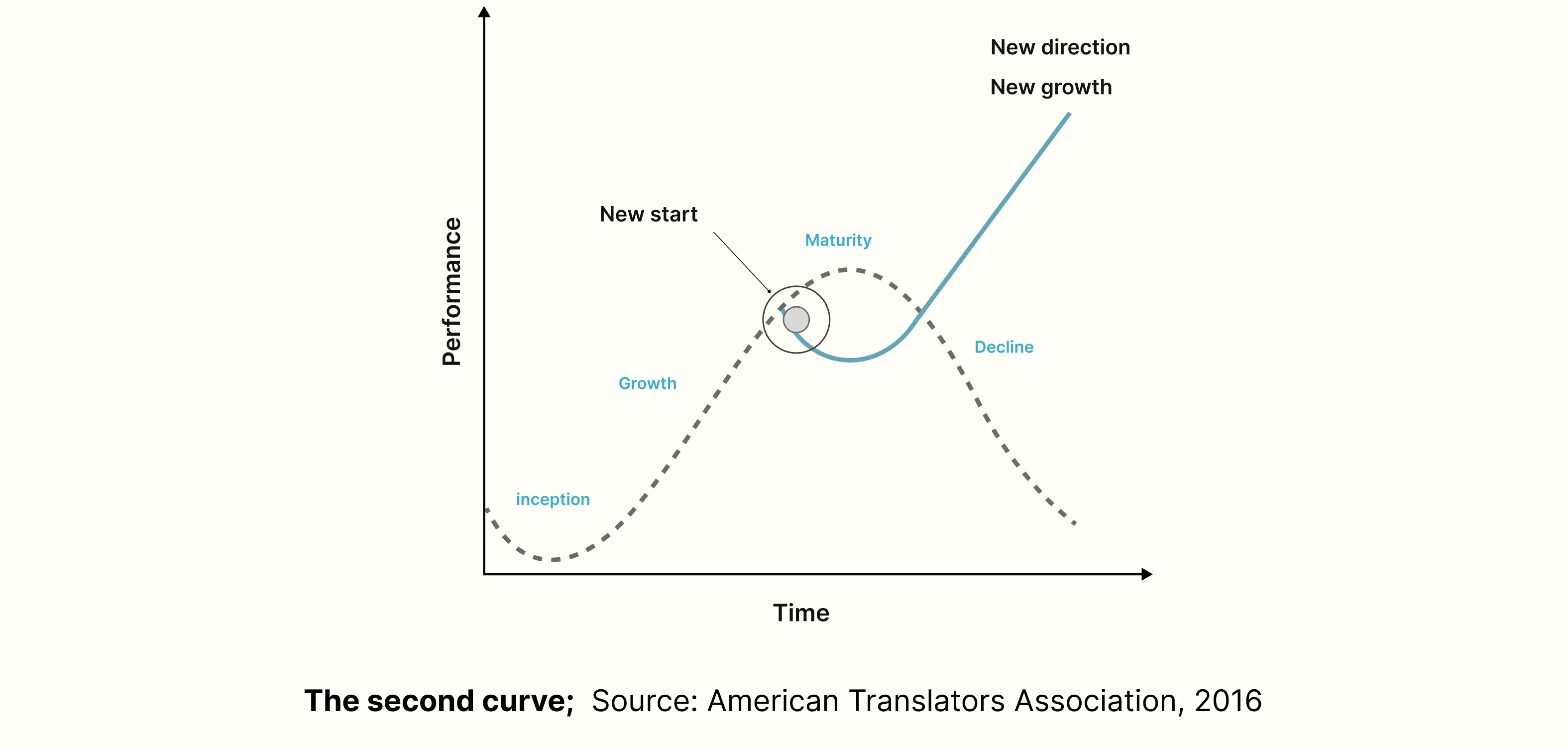

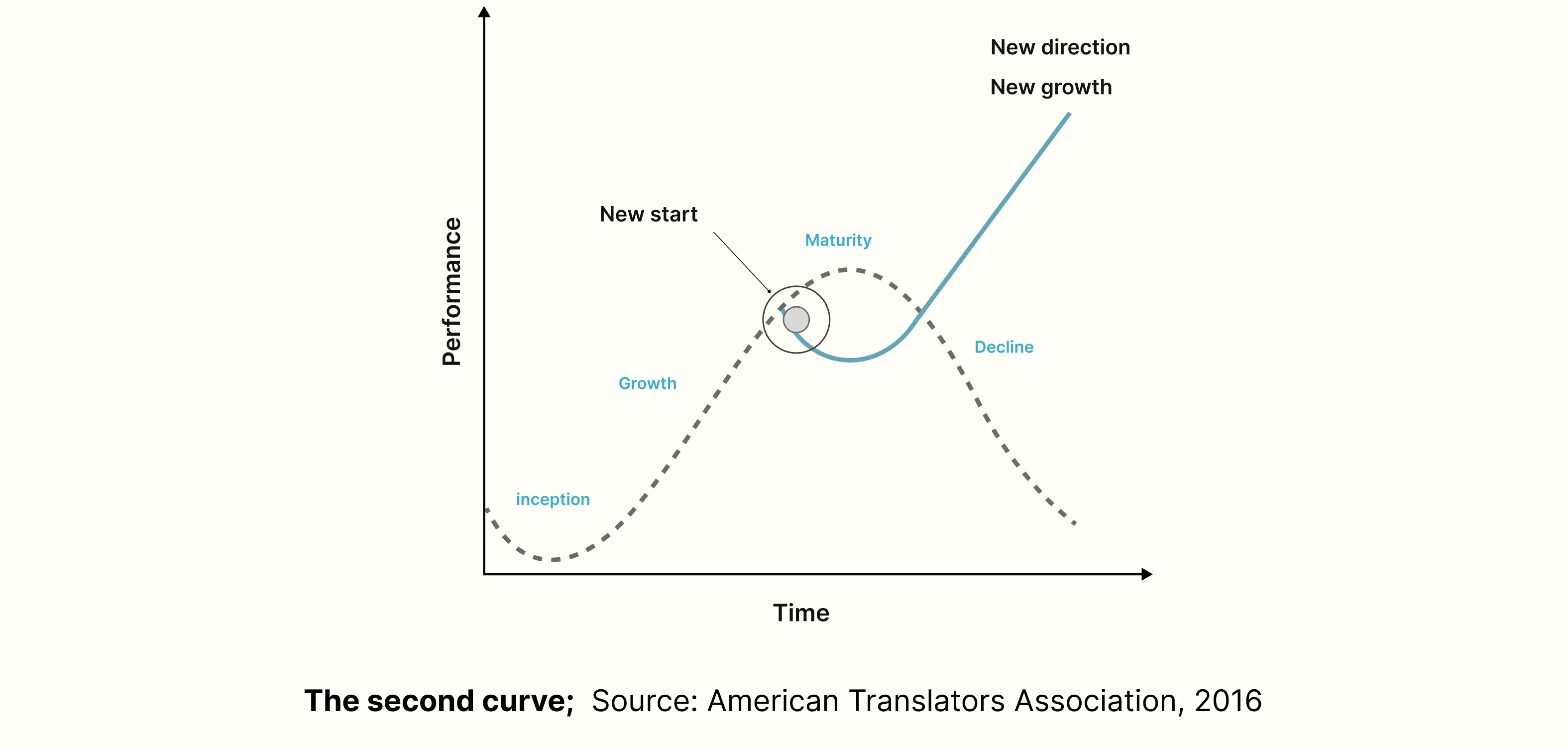

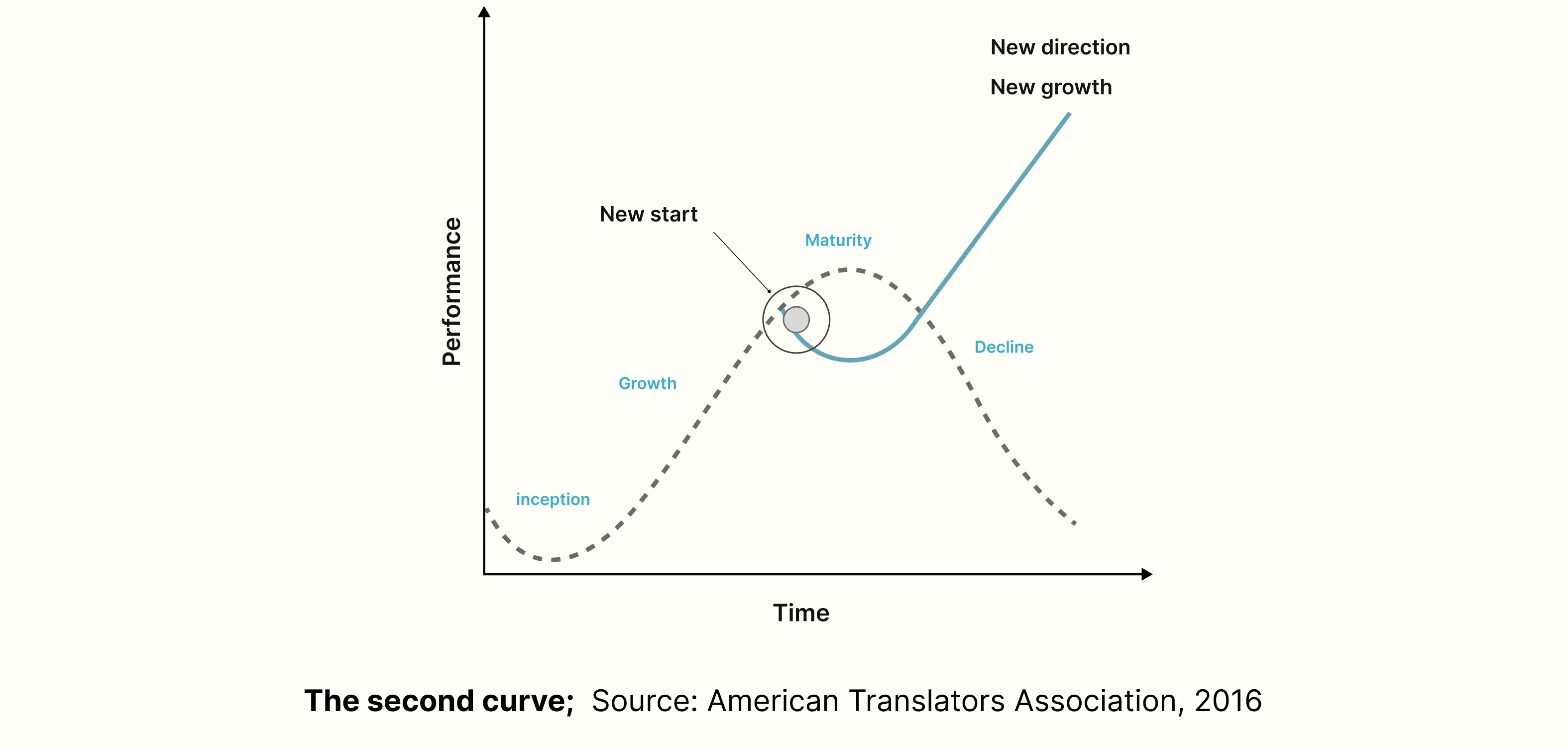

To cross from your current peak to a higher one, you must traverse this valley, where you will look and feel like a novice. Charles Handy's concept of the Second Curve illustrates this perfectly. To build the future, you must start a new trajectory while the old one is still peaking, which necessitates a period where the new effort performs worse than the old one.

I am good at building companies. I understood unit economics, regulatory frameworks, and product-market fit. When I speak in those domains, I speak with authority. Writing is different.Every Monday, I'm building that authority from zero. The founder who "has it figured out" doesn'texist in this domain. Only the writer who's learning exists.

The only thing preventing the leap across the moat is ego, not ability. Enduring a momentary loss of status is the price of admission to long-term leverage.

You can't build agency without crossing moats

Researcher Cate Hall has written extensively about the relationship between the Low StatusMoat and agency. Her insight is simple but profound: You cannot build agency without repeatedly crossing low-status moats.

Here's why: Agency is the ability to learn what needs to be learned, build what needs to be built, and solve problems you don't yet know how to solve.

When you refuse to cross the Low Status Moat, you're capping your agency at the boundaries of your current expertise. You can execute. You can optimise. But you can't expand your capacity to shape outcomes beyond what you already know.

The good leader looks at the moat and retreats. They calculate that the cost of looking like a novice is too high. Their agency is bound by their existing expertise.

The great leader understands the moat as an untouched opportunity whereas 99% of people are biologically wired to avoid the social pain of looking incompetent.

By crossing moats repeatedly, you build two things that compound agency:

Learning compounds exponentially. The first moat crossing is brutal. The second is still uncomfortable, but you've built the muscle. By the tenth, you're not just collecting skills but building meta-capability, the ability to learn anything. The person who's crossed ten moats can cross the eleventh faster than someone crossing their first. This is agency at scale, the ability to rapidly acquire whatever competence the problem demands.

Surface area of luck expands. When you learn in public, new opportunities you couldn't have predicted emerge. Great careers aren't linear. They're combinatorial. Fintech + writing + public learning creates a unique position nobody else can occupy. This expanded surface area is what turns agency from individual capability into network effect.

Why crossing the Low Status Moat feels impossible

If crossing moats builds agency, why do so few people do it? Because the moat isn't just inconvenient. It's biologically engineered to feel like death. The resistance to crossing isn't in your head. It's built into three interlocking systems:

The biology of threat

When you're about to publish work that reveals you're a beginner, your brain doesn't politely register vulnerability. It detects a survival threat. Neurobiologically, social rejection and status loss activate the same neural alarm systems as physical danger. The amygdala floods your system with stress hormones. These shut down the prefrontal cortex - the CEO of your brain, responsible for executive function and strategic planning. Avoiding the "pain" of looking incompetent while building agency is what keeps good performers stuck at good.

The conditioning of competence

Research shows that kids praised for intelligence develop "performance-contingent self-esteem" , and when they encounter difficulty, they protect identity instead of expanding capability. In classic studies, these children were 67% more likely to choose easier tasks to avoid looking stupid.

As adults, this calcifies into the executive who can't say "I don't know" , the founder who doubles down on a failing strategy rather than admit error, the accomplished professional who can't start something new because being a beginner feels like identity death.

I see this in myself every Monday. The urge not to post isn't about the work being unready. It's about what posting reveals: that I'm still learning. For someone who built identity on being competent, being visibly incompetent feels like dismantling oneself in public.

The illusion of effortless success

We only see the glamour of published books, viral posts, or polished final products. We don't see the shitty first drafts. We don't see the low status moat that every successful person crossed to get where they are. Social media perfects this distortion. The algorithm rewards polished performance and punishes visible struggle. What we consume daily is a highlight reel of other people's mastery, with all evidence of their learning process edited out. This creates a devastating comparison trap. When I see another writer's essay going viral, I don't see the hundred essays written before it. I see effortless excellence, and my brain screams: "Don't post this. Everyone else has it figured out. You're the only one struggling."

How to cross the Low Status Moat

Understanding why crossing builds agency is necessary but not sufficient. You still need the protocol for actually crossing when your amygdala is screaming.

The 90-second rule

Neuroscientist Jill Bolte Taylor found that the physiological lifespan of an emotional reaction is approximately 90 seconds. When a threat triggers fight-or-flight, stress hormones surge and flush out in that window. Any shame or anger you feel after 90 seconds is self-generated. It's your internal narrator replaying the insult, triggering fresh chemical dumps.

This changes everything. The initial flush - stomach drop, racing heart, heat in face - those are biological reflexes. You cannot stop them. But you can choose not to extend them.

The strategy: Pause. Do nothing for 90 seconds. Don't send the defensive email. Don't snap back. Don't delete the post. Let the wave crest and break.

Once chemicals subside, your prefrontal cortex comes back online. You can respond with strategy rather than reflex

Decouple identity from output

You must decouple your identity from your current capability. I stopped being "the founder who knows" and became "the founder who learns. " When you separate who you are from what you produce, critical feedback becomes data to optimise the product, not a weapon to wound the self.

Court rejection deliberately

You can't desensitise to the moat by avoiding it. I chose to publish weekly, knowing some pieces would be weak. Not for humility performance but to build the muscle of crossing. Each Monday is a rep. The first time you cross a moat, it's brutal. The tenth time, your amygdala still screams, but you know the scream passes. You've survived looking foolish before. You'll survive it again.

Mine for feedback

Most people avoid feedback to protect their ego. But feedback is the only way to know if you're crossing the moat or just wandering in circles. I don't wait for feedback to find me. I ask for it."What didn't work in this piece?" "Where did I lose you?" "What should I read to get better at this?" This flips the script. Instead of defending against feedback, you're mining for it. Because feedback is the signal that tells you how fast you're learning.

The Moat Is The Point

I still feel my stomach drop when I'm about to post. The difference is I now understand what that feeling means. It's not a warning to stop. It's confirmation I'm in the right place, because if it doesn't sting, I'm not in the moat. And if I'm not in the moat, I'm not building agency.

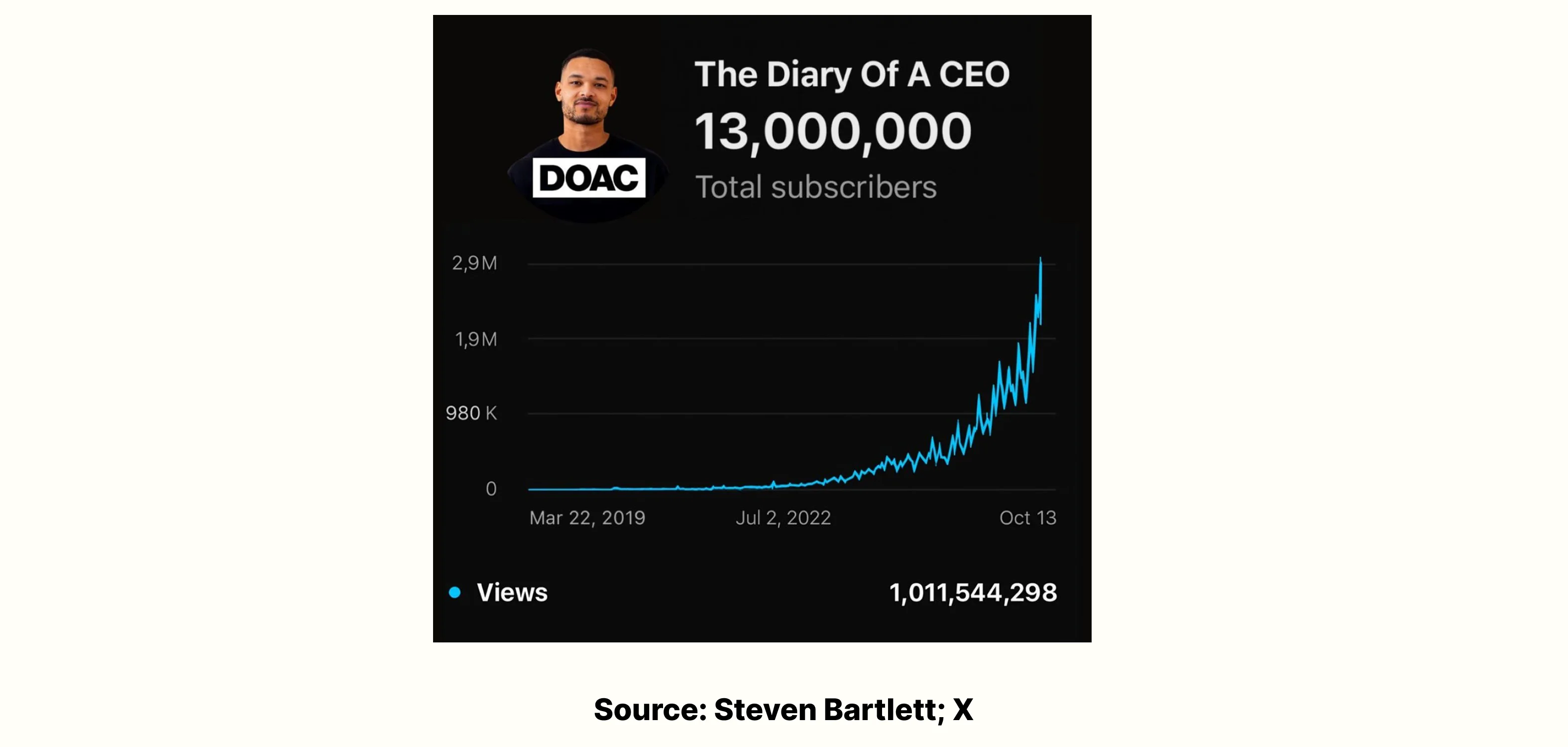

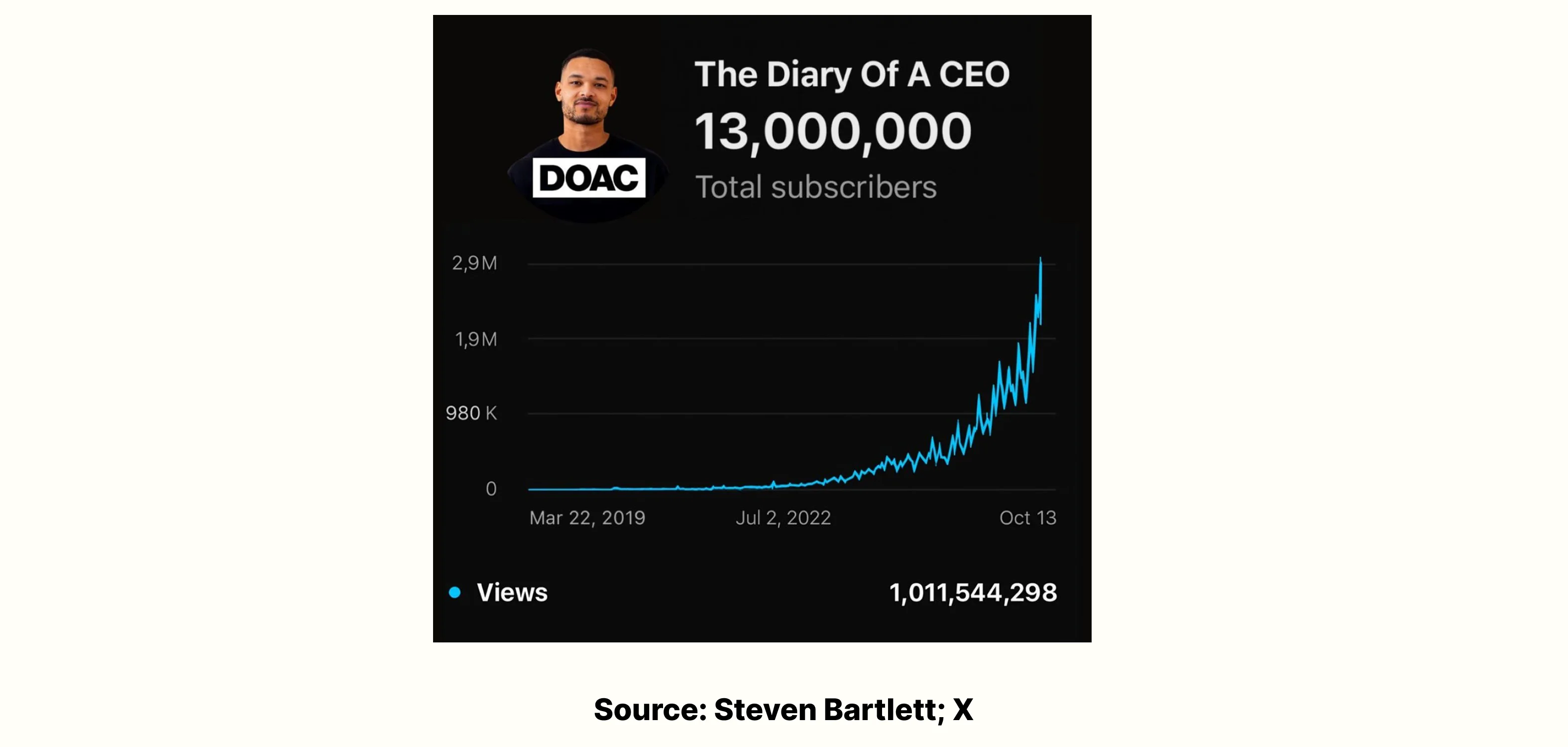

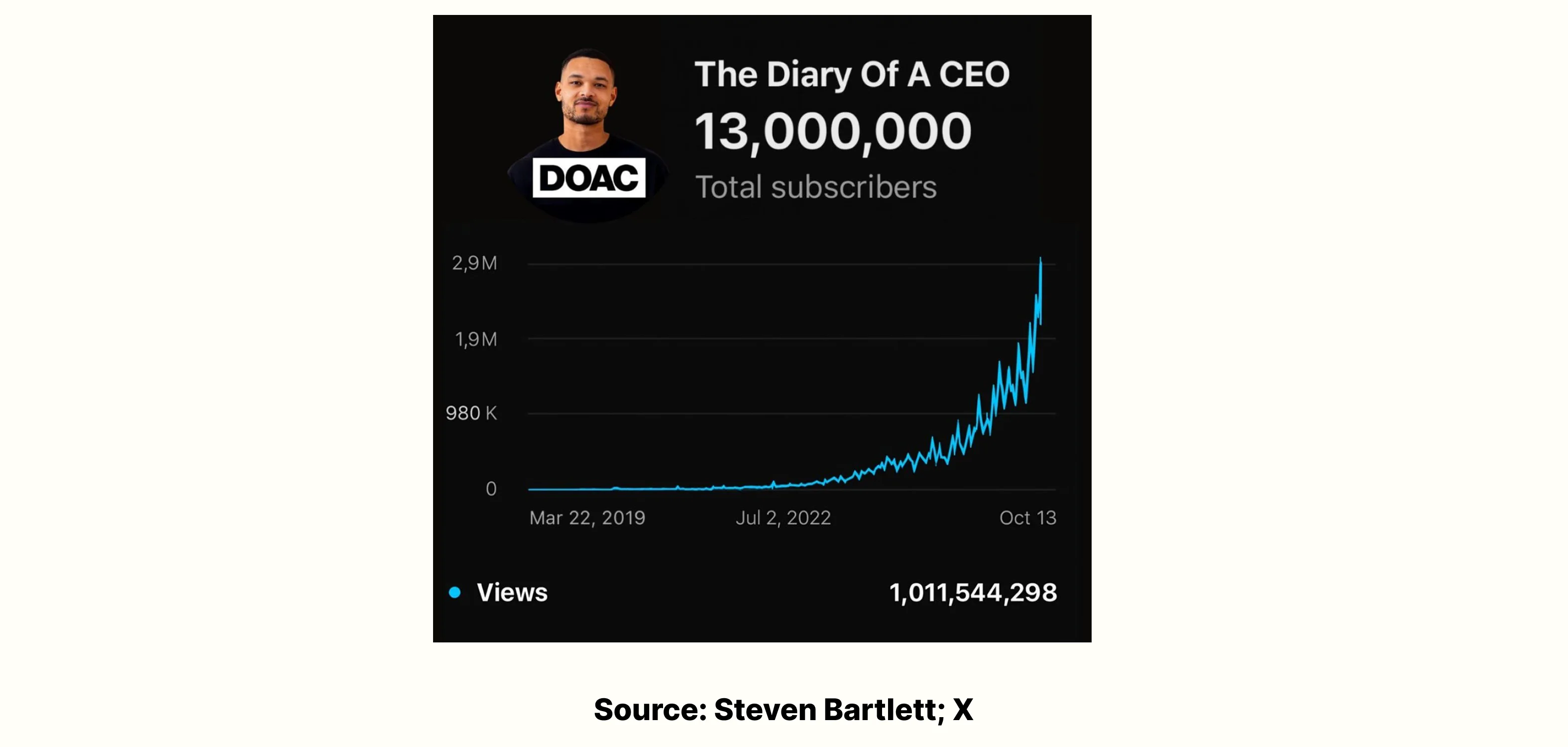

Darwin spent decades quietly building evidence before On the Origin of Species changed the world. Steven Bartlett started Diary of a CEO as a side experiment before it became one of the world’s biggest business podcasts.

They crossed anyway. Because they understood: The Low Status Moat isn't an obstacle to agency. It's the only place where agency gets built.

So every Monday morning, when my brain screams to protect my status by not posting,I recognise it for what it is: An ancient system trying to keep me safe by capping my agency.

I feel the 90 seconds. And then I cross anyway. Not because I'm brave. Because I understand that agency isn't built by protecting what you know. It's built by repeatedly entering moats where you don't know.

Now go find a moat to cross today.

That's how you build agency. And agency is how good becomes great.

High performers need to cross it to build agency

Why do high performers find it increasingly hard to perform even better? Because the difference between good and great is the willingness to repeatedly cross the valley where competence drops, and status disappears. This valley is an invisible moat which most high performers are not willing to cross because it calls for travelling through an uncharted territory. An overabundance of status protection, triggered by an evolutionary neurological mechanism, prevents them from taking unnecessary risks. Converging research from neurobiology, behavioural economics, and network science suggests that the only thing preventing a leap across this biological moat is ego, not ability.

This is how I am crossing my moat.

I'm a founder. I've raised capital, built companies, and survived an acquisition. But everyMonday morning, my stomach drops, because I have been trying to cross a different moat. Writing. This very newsletter.

I've pitched VCs, managed crises, and made payroll when the bank account was empty. None of that made my hands sweat the way hitting "publish" on a piece of writing does. Because when I write, I'm not in my domain of mastery anymore. I'm a novice. A founder trying to become a writer. A similar story was narrated by a friend, a technology leader who's built AI systems at scale. He's terrified to post on LinkedIn. "I can talk about this stuff in my sleep," he told me. "But posting a thought on AI? I rewrite it seventeen times and never publish. What will people think?"

When you're world-class at one thing, your brain over-indexes on protecting your existing reputation capital. Think of reputation as a portfolio. When you consider learning something new, your brain runs a calculation: "If I try this and am bad at it, I'm not just failing at the new thing but devaluing my entire portfolio. " This calculation is rational. Protect your assets. Don't take unnecessary risks.

By hitting the publish button, I am taking an unnecessary risk. But, what I've learned - and what every founder who's made multiple leaps has learned - is that greatness requires repeatedly crossing something I call the Low Status Moat.

The geography of growth

When you move from one domain of mastery to a new one, you inevitably enter an uncharted valley where your competence, efficiency and status are no good at survival.

This is the Low Status Moat.

To cross from your current peak to a higher one, you must traverse this valley, where you will look and feel like a novice. Charles Handy's concept of the Second Curve illustrates this perfectly. To build the future, you must start a new trajectory while the old one is still peaking, which necessitates a period where the new effort performs worse than the old one.

I am good at building companies. I understood unit economics, regulatory frameworks, and product-market fit. When I speak in those domains, I speak with authority. Writing is different.Every Monday, I'm building that authority from zero. The founder who "has it figured out" doesn'texist in this domain. Only the writer who's learning exists.

The only thing preventing the leap across the moat is ego, not ability. Enduring a momentary loss of status is the price of admission to long-term leverage.

You can't build agency without crossing moats

Researcher Cate Hall has written extensively about the relationship between the Low StatusMoat and agency. Her insight is simple but profound: You cannot build agency without repeatedly crossing low-status moats.

Here's why: Agency is the ability to learn what needs to be learned, build what needs to be built, and solve problems you don't yet know how to solve.

When you refuse to cross the Low Status Moat, you're capping your agency at the boundaries of your current expertise. You can execute. You can optimise. But you can't expand your capacity to shape outcomes beyond what you already know.

The good leader looks at the moat and retreats. They calculate that the cost of looking like a novice is too high. Their agency is bound by their existing expertise.

The great leader understands the moat as an untouched opportunity whereas 99% of people are biologically wired to avoid the social pain of looking incompetent.

By crossing moats repeatedly, you build two things that compound agency:

Learning compounds exponentially. The first moat crossing is brutal. The second is still uncomfortable, but you've built the muscle. By the tenth, you're not just collecting skills but building meta-capability, the ability to learn anything. The person who's crossed ten moats can cross the eleventh faster than someone crossing their first. This is agency at scale, the ability to rapidly acquire whatever competence the problem demands.

Surface area of luck expands. When you learn in public, new opportunities you couldn't have predicted emerge. Great careers aren't linear. They're combinatorial. Fintech + writing + public learning creates a unique position nobody else can occupy. This expanded surface area is what turns agency from individual capability into network effect.

Why crossing the Low Status Moat feels impossible

If crossing moats builds agency, why do so few people do it? Because the moat isn't just inconvenient. It's biologically engineered to feel like death. The resistance to crossing isn't in your head. It's built into three interlocking systems:

The biology of threat

When you're about to publish work that reveals you're a beginner, your brain doesn't politely register vulnerability. It detects a survival threat. Neurobiologically, social rejection and status loss activate the same neural alarm systems as physical danger. The amygdala floods your system with stress hormones. These shut down the prefrontal cortex - the CEO of your brain, responsible for executive function and strategic planning. Avoiding the "pain" of looking incompetent while building agency is what keeps good performers stuck at good.

The conditioning of competence

Research shows that kids praised for intelligence develop "performance-contingent self-esteem" , and when they encounter difficulty, they protect identity instead of expanding capability. In classic studies, these children were 67% more likely to choose easier tasks to avoid looking stupid.

As adults, this calcifies into the executive who can't say "I don't know" , the founder who doubles down on a failing strategy rather than admit error, the accomplished professional who can't start something new because being a beginner feels like identity death.

I see this in myself every Monday. The urge not to post isn't about the work being unready. It's about what posting reveals: that I'm still learning. For someone who built identity on being competent, being visibly incompetent feels like dismantling oneself in public.

The illusion of effortless success

We only see the glamour of published books, viral posts, or polished final products. We don't see the shitty first drafts. We don't see the low status moat that every successful person crossed to get where they are. Social media perfects this distortion. The algorithm rewards polished performance and punishes visible struggle. What we consume daily is a highlight reel of other people's mastery, with all evidence of their learning process edited out. This creates a devastating comparison trap. When I see another writer's essay going viral, I don't see the hundred essays written before it. I see effortless excellence, and my brain screams: "Don't post this. Everyone else has it figured out. You're the only one struggling."

How to cross the Low Status Moat

Understanding why crossing builds agency is necessary but not sufficient. You still need the protocol for actually crossing when your amygdala is screaming.

The 90-second rule

Neuroscientist Jill Bolte Taylor found that the physiological lifespan of an emotional reaction is approximately 90 seconds. When a threat triggers fight-or-flight, stress hormones surge and flush out in that window. Any shame or anger you feel after 90 seconds is self-generated. It's your internal narrator replaying the insult, triggering fresh chemical dumps.

This changes everything. The initial flush - stomach drop, racing heart, heat in face - those are biological reflexes. You cannot stop them. But you can choose not to extend them.

The strategy: Pause. Do nothing for 90 seconds. Don't send the defensive email. Don't snap back. Don't delete the post. Let the wave crest and break.

Once chemicals subside, your prefrontal cortex comes back online. You can respond with strategy rather than reflex

Decouple identity from output

You must decouple your identity from your current capability. I stopped being "the founder who knows" and became "the founder who learns. " When you separate who you are from what you produce, critical feedback becomes data to optimise the product, not a weapon to wound the self.

Court rejection deliberately

You can't desensitise to the moat by avoiding it. I chose to publish weekly, knowing some pieces would be weak. Not for humility performance but to build the muscle of crossing. Each Monday is a rep. The first time you cross a moat, it's brutal. The tenth time, your amygdala still screams, but you know the scream passes. You've survived looking foolish before. You'll survive it again.

Mine for feedback

Most people avoid feedback to protect their ego. But feedback is the only way to know if you're crossing the moat or just wandering in circles. I don't wait for feedback to find me. I ask for it."What didn't work in this piece?" "Where did I lose you?" "What should I read to get better at this?" This flips the script. Instead of defending against feedback, you're mining for it. Because feedback is the signal that tells you how fast you're learning.

The Moat Is The Point

I still feel my stomach drop when I'm about to post. The difference is I now understand what that feeling means. It's not a warning to stop. It's confirmation I'm in the right place, because if it doesn't sting, I'm not in the moat. And if I'm not in the moat, I'm not building agency.

Darwin spent decades quietly building evidence before On the Origin of Species changed the world. Steven Bartlett started Diary of a CEO as a side experiment before it became one of the world’s biggest business podcasts.

They crossed anyway. Because they understood: The Low Status Moat isn't an obstacle to agency. It's the only place where agency gets built.

So every Monday morning, when my brain screams to protect my status by not posting,I recognise it for what it is: An ancient system trying to keep me safe by capping my agency.

I feel the 90 seconds. And then I cross anyway. Not because I'm brave. Because I understand that agency isn't built by protecting what you know. It's built by repeatedly entering moats where you don't know.

Now go find a moat to cross today.

That's how you build agency. And agency is how good becomes great.

The Low Status

Moat Matters

High performers need to cross it to build agency

Why do high performers find it increasingly hard to perform even better? Because the difference between good and great is the willingness to repeatedly cross the valley where competence drops, and status disappears. This valley is an invisible moat which most high performers are not willing to cross because it calls for travelling through an uncharted territory. An overabundance of status protection, triggered by an evolutionary neurological mechanism, prevents them from taking unnecessary risks. Converging research from neurobiology, behavioural economics, and network science suggests that the only thing preventing a leap across this biological moat is ego, not ability.

This is how I am crossing my moat.

I'm a founder. I've raised capital, built companies, and survived an acquisition. But everyMonday morning, my stomach drops, because I have been trying to cross a different moat. Writing. This very newsletter.

I've pitched VCs, managed crises, and made payroll when the bank account was empty. None of that made my hands sweat the way hitting "publish" on a piece of writing does. Because when I write, I'm not in my domain of mastery anymore. I'm a novice. A founder trying to become a writer. A similar story was narrated by a friend, a technology leader who's built AI systems at scale. He's terrified to post on LinkedIn. "I can talk about this stuff in my sleep," he told me. "But posting a thought on AI? I rewrite it seventeen times and never publish. What will people think?"

When you're world-class at one thing, your brain over-indexes on protecting your existing reputation capital. Think of reputation as a portfolio. When you consider learning something new, your brain runs a calculation: "If I try this and am bad at it, I'm not just failing at the new thing but devaluing my entire portfolio. " This calculation is rational. Protect your assets. Don't take unnecessary risks.

By hitting the publish button, I am taking an unnecessary risk. But, what I've learned - and what every founder who's made multiple leaps has learned - is that greatness requires repeatedly crossing something I call the Low Status Moat.

The geography of growth

When you move from one domain of mastery to a new one, you inevitably enter an uncharted valley where your competence, efficiency and status are no good at survival.

This is the Low Status Moat.

To cross from your current peak to a higher one, you must traverse this valley, where you will look and feel like a novice. Charles Handy's concept of the Second Curve illustrates this perfectly. To build the future, you must start a new trajectory while the old one is still peaking, which necessitates a period where the new effort performs worse than the old one.

I am good at building companies. I understood unit economics, regulatory frameworks, and product-market fit. When I speak in those domains, I speak with authority. Writing is different.Every Monday, I'm building that authority from zero. The founder who "has it figured out" doesn'texist in this domain. Only the writer who's learning exists.

The only thing preventing the leap across the moat is ego, not ability. Enduring a momentary loss of status is the price of admission to long-term leverage.

You can't build agency without crossing moats

Researcher Cate Hall has written extensively about the relationship between the Low StatusMoat and agency. Her insight is simple but profound: You cannot build agency without repeatedly crossing low-status moats.

Here's why: Agency is the ability to learn what needs to be learned, build what needs to be built, and solve problems you don't yet know how to solve.

When you refuse to cross the Low Status Moat, you're capping your agency at the boundaries of your current expertise. You can execute. You can optimise. But you can't expand your capacity to shape outcomes beyond what you already know.

The good leader looks at the moat and retreats. They calculate that the cost of looking like a novice is too high. Their agency is bound by their existing expertise.

The great leader understands the moat as an untouched opportunity whereas 99% of people are biologically wired to avoid the social pain of looking incompetent.

By crossing moats repeatedly, you build two things that compound agency:

Learning compounds exponentially. The first moat crossing is brutal. The second is still uncomfortable, but you've built the muscle. By the tenth, you're not just collecting skills but building meta-capability, the ability to learn anything. The person who's crossed ten moats can cross the eleventh faster than someone crossing their first. This is agency at scale, the ability to rapidly acquire whatever competence the problem demands.

Surface area of luck expands. When you learn in public, new opportunities you couldn't have predicted emerge. Great careers aren't linear. They're combinatorial. Fintech + writing + public learning creates a unique position nobody else can occupy. This expanded surface area is what turns agency from individual capability into network effect.

Why crossing the Low Status Moat feels impossible

If crossing moats builds agency, why do so few people do it? Because the moat isn't just inconvenient. It's biologically engineered to feel like death. The resistance to crossing isn't in your head. It's built into three interlocking systems:

The biology of threat

When you're about to publish work that reveals you're a beginner, your brain doesn't politely register vulnerability. It detects a survival threat. Neurobiologically, social rejection and status loss activate the same neural alarm systems as physical danger. The amygdala floods your system with stress hormones. These shut down the prefrontal cortex - the CEO of your brain, responsible for executive function and strategic planning. Avoiding the "pain" of looking incompetent while building agency is what keeps good performers stuck at good.

The conditioning of competence

Research shows that kids praised for intelligence develop "performance-contingent self-esteem" , and when they encounter difficulty, they protect identity instead of expanding capability. In classic studies, these children were 67% more likely to choose easier tasks to avoid looking stupid.

As adults, this calcifies into the executive who can't say "I don't know" , the founder who doubles down on a failing strategy rather than admit error, the accomplished professional who can't start something new because being a beginner feels like identity death.

I see this in myself every Monday. The urge not to post isn't about the work being unready. It's about what posting reveals: that I'm still learning. For someone who built identity on being competent, being visibly incompetent feels like dismantling oneself in public.

The illusion of effortless success

We only see the glamour of published books, viral posts, or polished final products. We don't see the shitty first drafts. We don't see the low status moat that every successful person crossed to get where they are. Social media perfects this distortion. The algorithm rewards polished performance and punishes visible struggle. What we consume daily is a highlight reel of other people's mastery, with all evidence of their learning process edited out. This creates a devastating comparison trap. When I see another writer's essay going viral, I don't see the hundred essays written before it. I see effortless excellence, and my brain screams: "Don't post this. Everyone else has it figured out. You're the only one struggling."

How to cross the Low Status Moat

Understanding why crossing builds agency is necessary but not sufficient. You still need the protocol for actually crossing when your amygdala is screaming.

The 90-second rule

Neuroscientist Jill Bolte Taylor found that the physiological lifespan of an emotional reaction is approximately 90 seconds. When a threat triggers fight-or-flight, stress hormones surge and flush out in that window. Any shame or anger you feel after 90 seconds is self-generated. It's your internal narrator replaying the insult, triggering fresh chemical dumps.

This changes everything. The initial flush - stomach drop, racing heart, heat in face - those are biological reflexes. You cannot stop them. But you can choose not to extend them.

The strategy: Pause. Do nothing for 90 seconds. Don't send the defensive email. Don't snap back. Don't delete the post. Let the wave crest and break.

Once chemicals subside, your prefrontal cortex comes back online. You can respond with strategy rather than reflex

Decouple identity from output

You must decouple your identity from your current capability. I stopped being "the founder who knows" and became "the founder who learns. " When you separate who you are from what you produce, critical feedback becomes data to optimise the product, not a weapon to wound the self.

Court rejection deliberately

You can't desensitise to the moat by avoiding it. I chose to publish weekly, knowing some pieces would be weak. Not for humility performance but to build the muscle of crossing. Each Monday is a rep. The first time you cross a moat, it's brutal. The tenth time, your amygdala still screams, but you know the scream passes. You've survived looking foolish before. You'll survive it again.

Mine for feedback

Most people avoid feedback to protect their ego. But feedback is the only way to know if you're crossing the moat or just wandering in circles. I don't wait for feedback to find me. I ask for it."What didn't work in this piece?" "Where did I lose you?" "What should I read to get better at this?" This flips the script. Instead of defending against feedback, you're mining for it. Because feedback is the signal that tells you how fast you're learning.

The Moat Is The Point

I still feel my stomach drop when I'm about to post. The difference is I now understand what that feeling means. It's not a warning to stop. It's confirmation I'm in the right place, because if it doesn't sting, I'm not in the moat. And if I'm not in the moat, I'm not building agency.

Darwin spent decades quietly building evidence before On the Origin of Species changed the world. Steven Bartlett started Diary of a CEO as a side experiment before it became one of the world’s biggest business podcasts.

They crossed anyway. Because they understood: The Low Status Moat isn't an obstacle to agency. It's the only place where agency gets built.

So every Monday morning, when my brain screams to protect my status by not posting,I recognise it for what it is: An ancient system trying to keep me safe by capping my agency.

I feel the 90 seconds. And then I cross anyway. Not because I'm brave. Because I understand that agency isn't built by protecting what you know. It's built by repeatedly entering moats where you don't know.

Now go find a moat to cross today.

That's how you build agency. And agency is how good becomes great.

Resonating with this philosophy?

Join the smartest founders mastering the inner game to face the unknown. Read by YC & Sequoia.

To be continued…

A small favor...

I don't run ads. If this brought clarity, the biggest favor you can do is subscribe below.

.svg)

.svg)