Heroes Ask for Help

Here is the single most damaging myth in professional life:

that asking for help is an admission of failure. We operate under the assumption that a bold request signals weakness, incompetence, or lack of preparedness.

The data shows the inverse is true.

Research from Harvard Business School and Wharton, led by Brooks, Gino, and Schweitzer, discovered a counterintuitive truth when studying thousands of professionals: people who asked for advice were rated as more competent than those who did not ask. Not slightly more. Significantly more. And the harder the problem, the smarter they looked for asking.

This article will show you why asking feels hard. What successful leaders do differently. And how to make the asks that change everything.

Here is the single most damaging myth in professional life:

that asking for help is an admission of failure. We operate under the assumption that a bold request signals weakness, incompetence, or lack of preparedness.

The data shows the inverse is true.

Research from Harvard Business School and Wharton, led by Brooks, Gino, and Schweitzer, discovered a counterintuitive truth when studying thousands of professionals: people who asked for advice were rated as more competent than those who did not ask. Not slightly more. Significantly more. And the harder the problem, the smarter they looked for asking.

This article will show you why asking feels hard. What successful leaders do differently. And how to make the asks that change everything.

The Inheritance of Silence I understand why asking feels hard because I spent the first thirty years of my life operating on the wrong side of it.

I grew up in a family where asking for anything was quietly discouraged. It's not that my parents ever said "don't ask for help" —they simply never did. They worked constantly, solved every problem themselves, and wore their self-reliance like armor. Money was tight. Resources were scarce. And the unspoken message was clear: strong people handle their problems independently.

By the time I was building my first startup, this had crystallized into identity. My claim to fame was that I had never asked my parents for money. Not once. Even when I was eating one meal a day, stomach empty and head spinning. Even when I had a stroke at 29 from the stress and still didn't ask for help. Even when I had three months of cash in the bank to make payroll.

I had a list of twelve people who had explicitly offered to help "if I ever needed anything. " I contacted exactly zero of them. Because asking would mean I wasn't capable. It would expose me as someone who couldn't execute independently. It would burden people who had better things to do.

The real question though is: What was I protecting? My pride. An identity built on childhood conditioning that had no bearing on building a successful company. I was optimizing for the wrong variable entirely.

Where This Fear Comes From

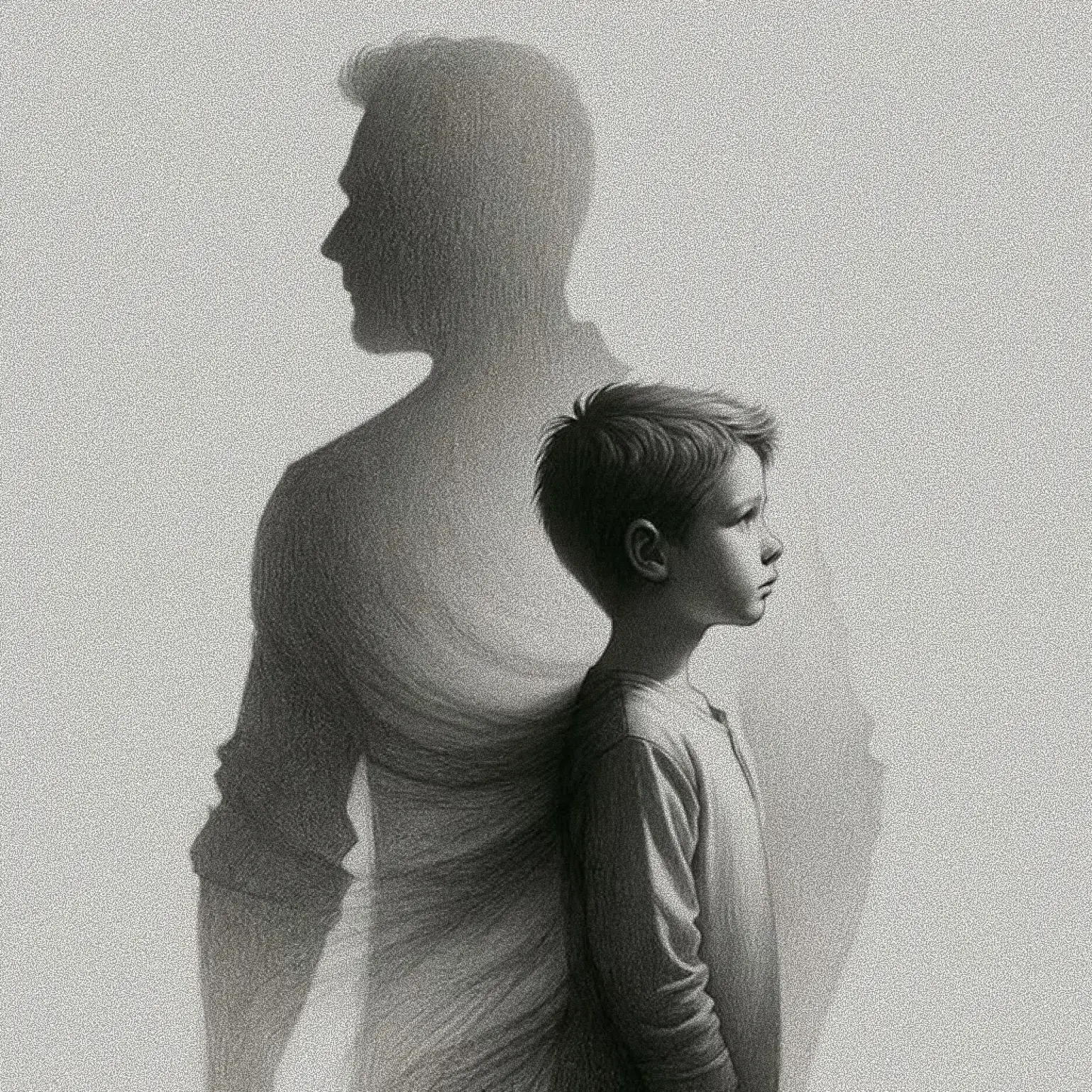

Our reluctance to ask doesn't come from nowhere. It's installed—by childhood, culture, and early career conditioning.

Childhood Scripts Many of us grew up with "good kid" programming. Be polite. Don't make trouble. Don't ask for too much. Psychologists call this personalization bias. If you grew up hearing "Handle it yourself" or "Don't be a burden," you internalized a message: my needs are problems.

Research from the University of Leipzig demonstrates that children exposed to coercive communication—"stop bothering me, " "you should be able to handle this yourself, " "I'm busy" —develop significantly different emotional responses than those raised with assertive communication. The child internalizes: asking is bad. I am bad for needing things. This persists into adulthood as the belief that asking makes you weak, needy, or burdensome.Cultural Reinforcement In cultures like India and other collectivist societies, the script is even stronger: Don't stand out. Don't disrupt harmony. Don't ask for special treatment. Approximately 60% of people in collectivist cultures exhibit asking-aversion because standing out—even to get help—risks bringing shame to the family or group.

First-generation immigrant entrepreneurs from these backgrounds face particular tension: their cultural upbringing says "don't make waves, " while Western entrepreneurship demands aggressive self-promotion and explicit asks.Growing Up Responsible If you were the kid who managed household crises, calmed your parents' nerves, or took care of younger siblings, you learned to suppress your own needs. You learned that asking created more problems than it solved.

Hooper's research shows this kind of role-reversal—called parentification—leads to adults who chronically over-function, feel guilty when receiving help, and struggle to articulate their own needs.

This compounds for first-generation achievers. Studies show imposter syndrome affects 76% of first-generation college students. The internal narrative: "I already got lucky getting in—I don't want to prove I don't belong."

The result: the people who most need mentorship, support, and feedback are the least likely to request it.

Dismantling the Cage: Why "Strong People Don't Ask" Is a Lie

These scripts create the belief that strong people don't ask. But every piece of evidence points in the opposite direction.

Evidence 1: Asking Makes You Look Smarter, Not Weaker Brooks, Gino, and Schweitzer's study across thousands of professionals found that individuals who seek advice are perceived as more competent than those who don't. The effect is strongest when the task is difficult—asking for help on hard problems actually boosts competence perception.

Why? Because asking signals meta-cognitive awareness. It demonstrates that you understand the complexity of the challenge and possess the strategic intelligence to gather resources before acting. Observers don't think "they're incompetent. " They think "they're smart enough to know what they don't know.

Evidence 2: People Want to Help More Than You Think Vanessa Bohns' research across more than 14,000 strangers with various requests found that people underestimate compliance likelihood by up to 50%. People estimated needing to ask 7.2 strangers to get one to escort them to the gym. Actual number needed: only 2.3 people—meaning every other person said yes.

Even for uncomfortable requests like vandalizing a library book, more than 64% of people complied despite expressing reluctance.

The mechanism: help-seekers focus on the cost to the helper—the time, the effort, the inconvenience. What we systematically fail to appreciate is the social cost of saying "no. " Refusing triggers guilt, threatens self-image as a helpful person, and creates awkwardness that most people prefer to avoid.

Recalibrate your expectations. If you think you need to ask five people to get one "yes, " the actual number is closer to two. Your pessimism about compliance rates is not realism—it's systematic miscalibration.

Evidence 3: Helpers Feel Better Than You Expect Zhao and Epley (2022) found across 2,118 participants that help-seekers underestimated how positively helpers would feel when asked and overestimated how inconvenienced they would be. Being asked to help satisfies basic psychological needs for relatedness, autonomy, and competence.

When you ask someone for help, you're not burdening them—you're giving them an opportunity to feel useful and valued.

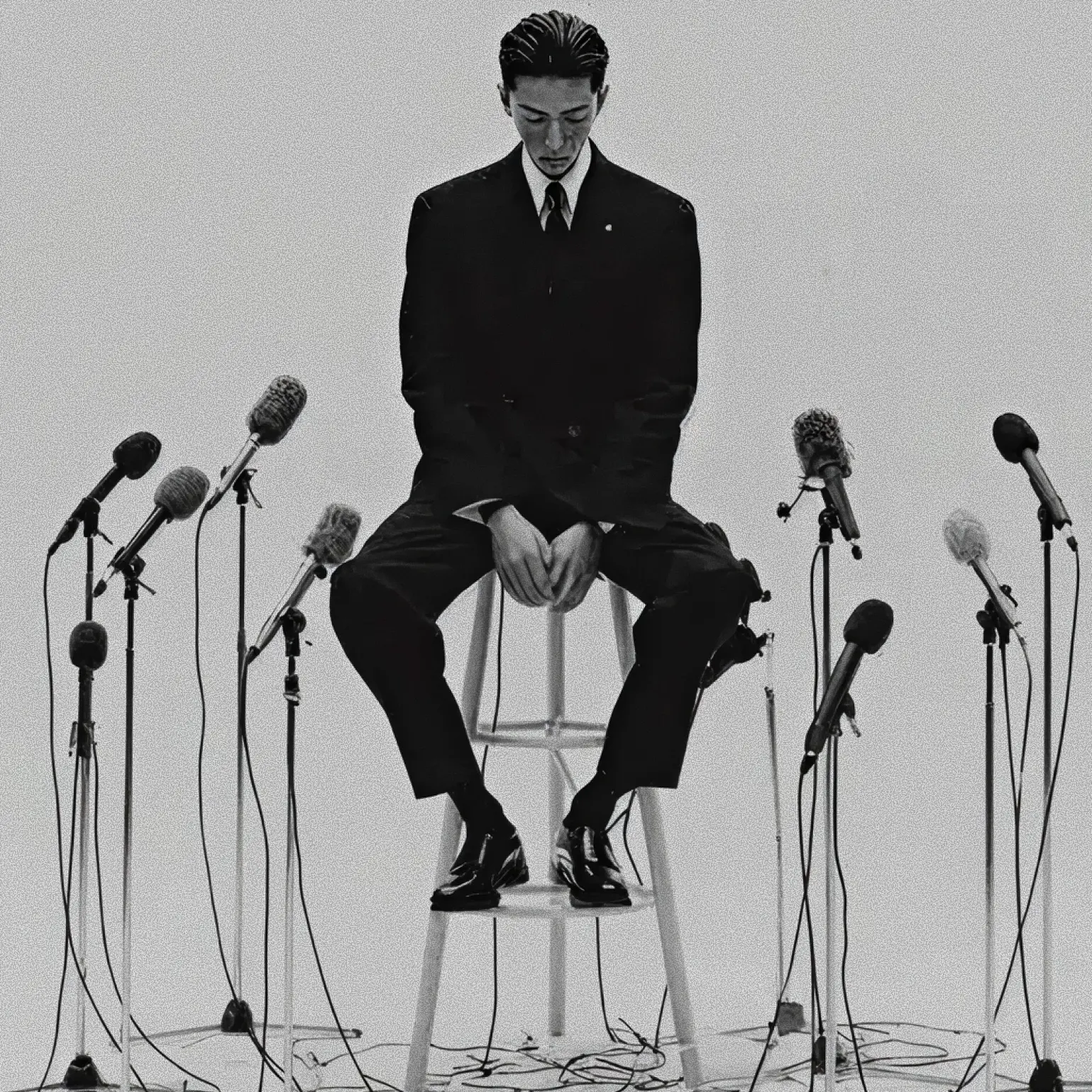

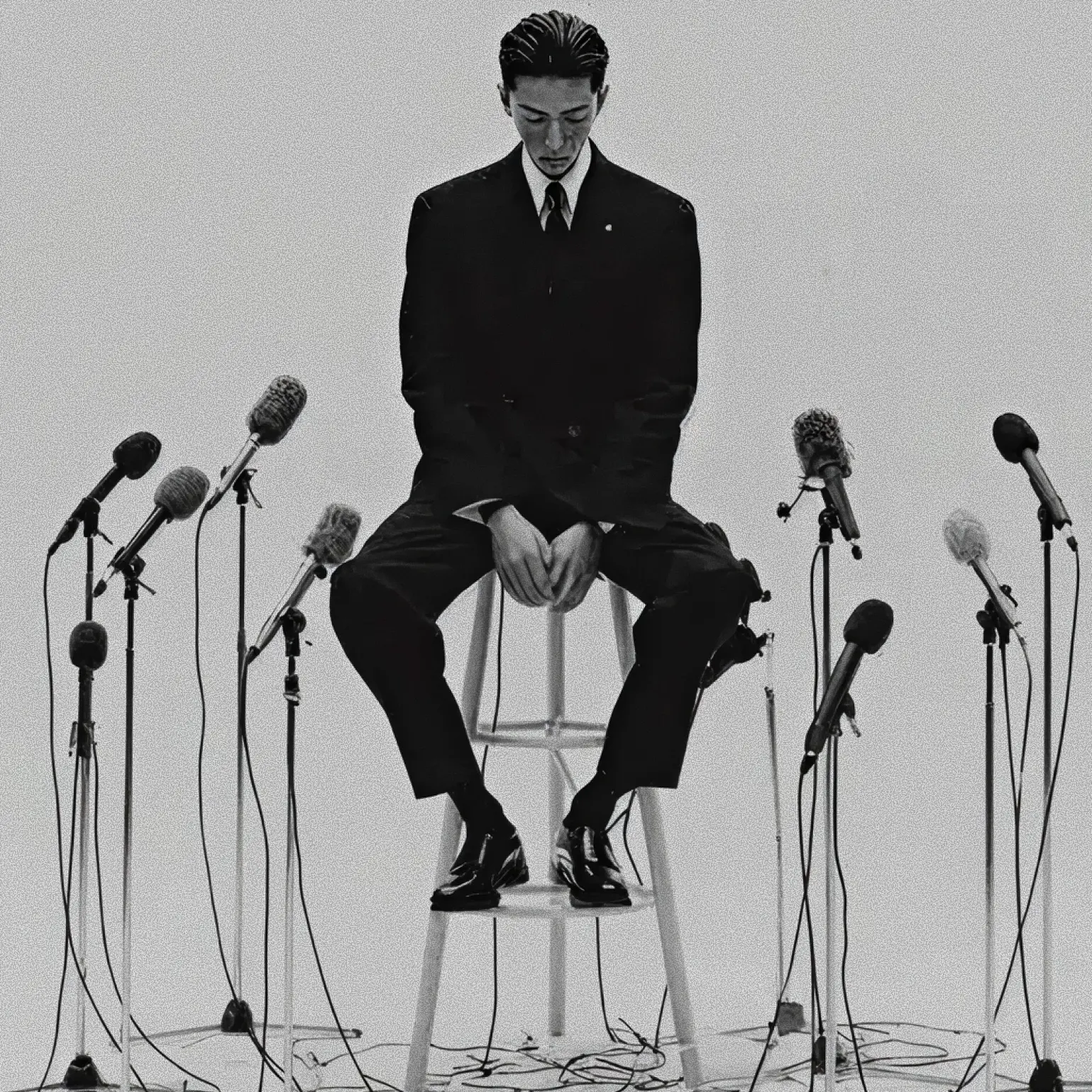

Evidence 4: Even Presidents Are Waiting to Be Asked Brian Chesky built Airbnb into an $80 billion company by systematically violating the assumptions most entrepreneurs accept about who you can ask for help.

When he wanted mentorship on community building, he asked himself: who is the most famous community organizer in the world? The answer was Barack Obama. Most founders would self-edit before typing the first sentence of that email, assuming a former President is categorically unreachable.

Chesky asked anyway. They established standing weekly one-hour calls. Obama gave him homework assignments. The relationship became one of the most valuable strategic assets in Airbnb's growth trajectory.

When Chesky asked Obama how many people he mentored, the answer was striking: "Hardly any." When he pressed for why, Obama's response demolished the core assumption that stops most people from asking: "Because no one asked me. "

This reveals a massive market inefficiency. High-status individuals are often under-utilized as mentors not because they lack availability or willingness, but because the market systematically assumes they are at capacity. The belief that "they are too busy" is a projection of the requester's insecurity, not a reflection of actual constraints.

The irony: busy, high-status individuals often prefer direct asks because they hate wasted time. A specific, well-structured request ("Could we discuss pricing strategy for two-sided marketplaces for 20 minutes on Thursday at 3 PM?") is easier to evaluate and respond to than vague relationship-building ("Let's grab coffee sometime").

Chesky's willingness to ask—to operate outside the boundaries most people accept—created asymmetric advantage. He accessed expertise, networks, and strategic guidance that competitors assumed was unavailable. The ask itself became competitive advantage.

The Principles of the Bold Request

Once we accept that the belief "strong people don't ask" is empirically false, we must operationalize the ask. Boldness is not just a mindset—it is a mechanical skill that can be optimized using behavioral science.

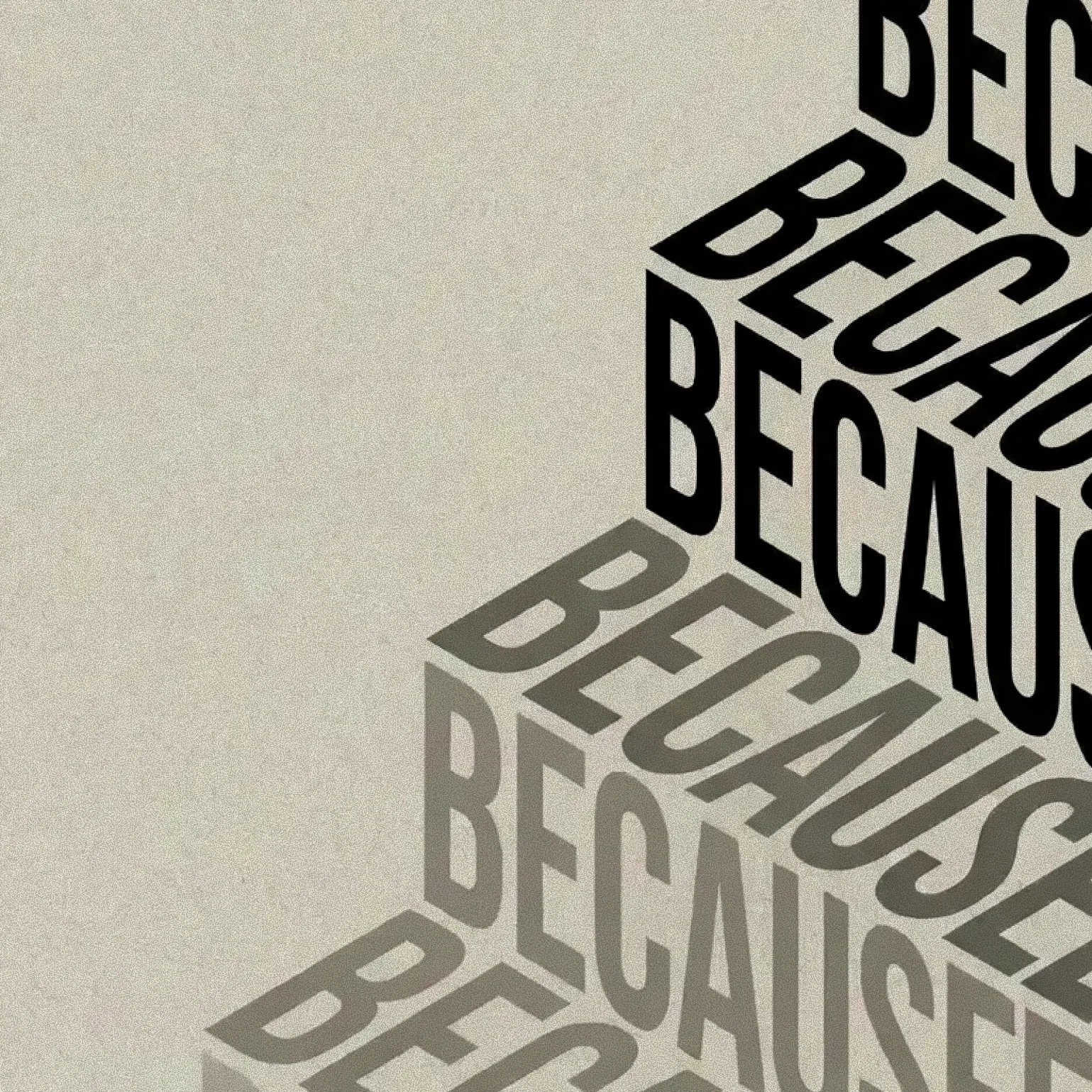

1. The "Because" Technique Increases Compliance 55% Ellen Langer's famous 1978 Harvard Xerox machine study found:1. Request only ("May I use the machine?"): 60% compliance2.Request + fake reason (" ...because I have to make copies"): 93% compliance3.Request + real reason (" ...because I'm in a rush"): 94% compliance

Simply including the word "because" followed by ANY explanation—even meaningless—increased compliance by 33 percentage points.

The mechanism: The human brain is wired for causal reasoning. Providing any explanation triggers a compliance script. The reason doesn't need to be compelling—it needs to exist.

Application: Never make a naked ask. Always include "because" followed by a reason: "I'm requesting 20 minutes because I'm facing a pricing decision in your domain and value your pattern recognition" vastly outperforms "Can we talk?"

2. "But You Are Free" Multiplies Compliance 4.75x Guéguen and Pascual (2000) found that adding "but you are free to accept or refuse" to a request for bus money increased compliance from 10% to 47.5%—a 375% increase. Meta-analysis of 52 studies (N=19,528) confirmed a medium effect size (g=0.44).

The mechanism: Acknowledging someone's freedom to decline paradoxically makes them more likely to accept. It removes psychological reactance—the instinctive resistance humans feel when autonomy is threatened.

Application: End requests with explicit acknowledgment of choice: "I would value your feedback on this deck, but you're completely free to decline if bandwidth doesn't permit. "

3. Small Requests Double Large-Request Compliance Freedman and Fraser's 1966 foot-in-the-door research found that without an initial request, only 22% of housewives agreed to let investigators enter their homes for 2 hours. With a brief questionnaire 3 days earlier, 43-53% agreed. When initial and follow-up requests were similar, compliance reached 76%.

The mechanism: Self-perception theory. Agreeing to a small request creates a self-image of "someone who helps this cause, " which people maintain through consistent behavior.

Application: If you want a major favor (introduction to a key investor), start with a small ask (feedback on your positioning). The initial "yes" creates momentum for larger requests.

4. Precision Signals Preparation Ambiguity creates cognitive load and triggers procrastination. Vague requests ("Can we grab coffee sometime?") require the recipient to do mental work. Specific requests ("Could we meet Thursday at 3 PM at Bluestone Lane for 30 minutes to discuss pricing strategy for B2B SaaS?") eliminate decision friction.

The mechanism: Research on negotiation demonstrates that precise numbers signal competence. Requesting $97,500 conveys analytical rigor. Requesting $100,000 suggests rough estimation.

Application: Replace "I'd love your advice" with "I need input on customer acquisition cost optimization for a two-sided marketplace—specifically whether to prioritize supply or demand in month one."

5. The Ben Franklin Effect: Asking Builds Relationships Jecker and Landy (1969) confirmed Benjamin Franklin's observation: people who do you a favor like you more afterward, not less. In their study, participants asked to return money to the researcher rated him 24% more likable than those who kept their money.

Franklin's original insight: "He that has once done you a kindness will be more ready to do you another, than he whom you yourself have obliged. "

The mechanism: Cognitive dissonance. When someone helps you, they rationalize the behavior: "I helped them, therefore I must like and value them. "

Application: Don't hoard favors. Asking for small favors early in a relationship actually strengthens it. Each ask that someone fulfills deepens their investment in your success.

The Cost of the Unasked Question Every avoided ask represents: 1.A skill not developed (asking becomes easier with practice)2.Information not gathered (even "no" provides data)3.A relationship not deepened (the Ben Franklin effect)A compounding opportunity foregone

The mathematics of compounding apply to networks and knowledge as much as capital. A single strategic introduction in year one can create partnerships, customers, and co-investors that reshape five-year trajectories. The professional who asks generates 48% more of these inflection points than the professional who waits to be noticed.

Every time you avoid asking, you're making a decision about what you deserve. You're saying implicitly that your needs matter less than someone else's convenience. That your company's survival is less important than avoiding a moment of discomfort. That preserving the illusion of self-sufficiency is worth the opportunity cost of the help you're not receiving.

Research by Davidai and Gilovich demonstrates that 76% of people's biggest life regrets concern inaction—things not done rather than mistakes made. Short-term, rejection stings. Long-term, unrealized potential haunts.

The Fortune of the Bold For the first thirty years of my life, I optimized for never needing help. The result: slower learning, smaller networks, years of unnecessary struggle. The moment I began asking—first with discomfort, then with systems—everything accelerated.

Five years later, I've asked for things I never thought I could. Introductions to investors who seemed unreachable. Advice from founders I admired. Strategic guidance when I was stuck. Asked Miss India on a date (she hasn't said yes yet). Raises that recognized my value. Favors from people I barely knew.

Roughly half said yes. Some became investors. Some became mentors. Some became friends. None of it would have happened if I'd waited for them to notice I needed help.

The difference between the founder who builds something meaningful and the founder who stays stuck isn't talent, capital, or timing. It's willingness to ask. To state clearly what you need. To give people the opportunity to help. To persist when the first answer is no.

Your brain will tell you asking is dangerous. Your childhood conditioning will tell you asking makes you needy. Your imposter syndrome will tell you that you don't deserve help.

The data says all of this is wrong.

As the Latin proverb states, Fortes fortuna adiuvat—fortune favors the bold. But fortune cannot favor you if you do not give it the opportunity.

Your next breakthrough exists on the other side of a question you haven't asked yet.

The Inheritance of Silence I understand why asking feels hard because I spent the first thirty years of my life operating on the wrong side of it.

I grew up in a family where asking for anything was quietly discouraged. It's not that my parents ever said "don't ask for help" —they simply never did. They worked constantly, solved every problem themselves, and wore their self-reliance like armor. Money was tight. Resources were scarce. And the unspoken message was clear: strong people handle their problems independently.

By the time I was building my first startup, this had crystallized into identity. My claim to fame was that I had never asked my parents for money. Not once. Even when I was eating one meal a day, stomach empty and head spinning. Even when I had a stroke at 29 from the stress and still didn't ask for help. Even when I had three months of cash in the bank to make payroll.

I had a list of twelve people who had explicitly offered to help "if I ever needed anything. " I contacted exactly zero of them. Because asking would mean I wasn't capable. It would expose me as someone who couldn't execute independently. It would burden people who had better things to do.

The real question though is: What was I protecting? My pride. An identity built on childhood conditioning that had no bearing on building a successful company. I was optimizing for the wrong variable entirely.

Where This Fear Comes From

Our reluctance to ask doesn't come from nowhere. It's installed—by childhood, culture, and early career conditioning.

Childhood Scripts Many of us grew up with "good kid" programming. Be polite. Don't make trouble. Don't ask for too much. Psychologists call this personalization bias. If you grew up hearing "Handle it yourself" or "Don't be a burden," you internalized a message: my needs are problems.

Research from the University of Leipzig demonstrates that children exposed to coercive communication—"stop bothering me, " "you should be able to handle this yourself, " "I'm busy" —develop significantly different emotional responses than those raised with assertive communication. The child internalizes: asking is bad. I am bad for needing things. This persists into adulthood as the belief that asking makes you weak, needy, or burdensome.Cultural Reinforcement In cultures like India and other collectivist societies, the script is even stronger: Don't stand out. Don't disrupt harmony. Don't ask for special treatment. Approximately 60% of people in collectivist cultures exhibit asking-aversion because standing out—even to get help—risks bringing shame to the family or group.

First-generation immigrant entrepreneurs from these backgrounds face particular tension: their cultural upbringing says "don't make waves, " while Western entrepreneurship demands aggressive self-promotion and explicit asks.Growing Up Responsible If you were the kid who managed household crises, calmed your parents' nerves, or took care of younger siblings, you learned to suppress your own needs. You learned that asking created more problems than it solved.

Hooper's research shows this kind of role-reversal—called parentification—leads to adults who chronically over-function, feel guilty when receiving help, and struggle to articulate their own needs.

This compounds for first-generation achievers. Studies show imposter syndrome affects 76% of first-generation college students. The internal narrative: "I already got lucky getting in—I don't want to prove I don't belong."

The result: the people who most need mentorship, support, and feedback are the least likely to request it.

Dismantling the Cage: Why "Strong People Don't Ask" Is a Lie

These scripts create the belief that strong people don't ask. But every piece of evidence points in the opposite direction.

Evidence 1: Asking Makes You Look Smarter, Not Weaker Brooks, Gino, and Schweitzer's study across thousands of professionals found that individuals who seek advice are perceived as more competent than those who don't. The effect is strongest when the task is difficult—asking for help on hard problems actually boosts competence perception.

Why? Because asking signals meta-cognitive awareness. It demonstrates that you understand the complexity of the challenge and possess the strategic intelligence to gather resources before acting. Observers don't think "they're incompetent. " They think "they're smart enough to know what they don't know.

Evidence 2: People Want to Help More Than You Think Vanessa Bohns' research across more than 14,000 strangers with various requests found that people underestimate compliance likelihood by up to 50%. People estimated needing to ask 7.2 strangers to get one to escort them to the gym. Actual number needed: only 2.3 people—meaning every other person said yes.

Even for uncomfortable requests like vandalizing a library book, more than 64% of people complied despite expressing reluctance.

The mechanism: help-seekers focus on the cost to the helper—the time, the effort, the inconvenience. What we systematically fail to appreciate is the social cost of saying "no. " Refusing triggers guilt, threatens self-image as a helpful person, and creates awkwardness that most people prefer to avoid.

Recalibrate your expectations. If you think you need to ask five people to get one "yes, " the actual number is closer to two. Your pessimism about compliance rates is not realism—it's systematic miscalibration.

Evidence 3: Helpers Feel Better Than You Expect Zhao and Epley (2022) found across 2,118 participants that help-seekers underestimated how positively helpers would feel when asked and overestimated how inconvenienced they would be. Being asked to help satisfies basic psychological needs for relatedness, autonomy, and competence.

When you ask someone for help, you're not burdening them—you're giving them an opportunity to feel useful and valued.

Evidence 4: Even Presidents Are Waiting to Be Asked Brian Chesky built Airbnb into an $80 billion company by systematically violating the assumptions most entrepreneurs accept about who you can ask for help.

When he wanted mentorship on community building, he asked himself: who is the most famous community organizer in the world? The answer was Barack Obama. Most founders would self-edit before typing the first sentence of that email, assuming a former President is categorically unreachable.

Chesky asked anyway. They established standing weekly one-hour calls. Obama gave him homework assignments. The relationship became one of the most valuable strategic assets in Airbnb's growth trajectory.

When Chesky asked Obama how many people he mentored, the answer was striking: "Hardly any." When he pressed for why, Obama's response demolished the core assumption that stops most people from asking: "Because no one asked me. "

This reveals a massive market inefficiency. High-status individuals are often under-utilized as mentors not because they lack availability or willingness, but because the market systematically assumes they are at capacity. The belief that "they are too busy" is a projection of the requester's insecurity, not a reflection of actual constraints.

The irony: busy, high-status individuals often prefer direct asks because they hate wasted time. A specific, well-structured request ("Could we discuss pricing strategy for two-sided marketplaces for 20 minutes on Thursday at 3 PM?") is easier to evaluate and respond to than vague relationship-building ("Let's grab coffee sometime").

Chesky's willingness to ask—to operate outside the boundaries most people accept—created asymmetric advantage. He accessed expertise, networks, and strategic guidance that competitors assumed was unavailable. The ask itself became competitive advantage.

The Principles of the Bold Request

Once we accept that the belief "strong people don't ask" is empirically false, we must operationalize the ask. Boldness is not just a mindset—it is a mechanical skill that can be optimized using behavioral science.

1. The "Because" Technique Increases Compliance 55% Ellen Langer's famous 1978 Harvard Xerox machine study found:1. Request only ("May I use the machine?"): 60% compliance2.Request + fake reason (" ...because I have to make copies"): 93% compliance3.Request + real reason (" ...because I'm in a rush"): 94% compliance

Simply including the word "because" followed by ANY explanation—even meaningless—increased compliance by 33 percentage points.

The mechanism: The human brain is wired for causal reasoning. Providing any explanation triggers a compliance script. The reason doesn't need to be compelling—it needs to exist.

Application: Never make a naked ask. Always include "because" followed by a reason: "I'm requesting 20 minutes because I'm facing a pricing decision in your domain and value your pattern recognition" vastly outperforms "Can we talk?"

2. "But You Are Free" Multiplies Compliance 4.75x Guéguen and Pascual (2000) found that adding "but you are free to accept or refuse" to a request for bus money increased compliance from 10% to 47.5%—a 375% increase. Meta-analysis of 52 studies (N=19,528) confirmed a medium effect size (g=0.44).

The mechanism: Acknowledging someone's freedom to decline paradoxically makes them more likely to accept. It removes psychological reactance—the instinctive resistance humans feel when autonomy is threatened.

Application: End requests with explicit acknowledgment of choice: "I would value your feedback on this deck, but you're completely free to decline if bandwidth doesn't permit. "

3. Small Requests Double Large-Request Compliance Freedman and Fraser's 1966 foot-in-the-door research found that without an initial request, only 22% of housewives agreed to let investigators enter their homes for 2 hours. With a brief questionnaire 3 days earlier, 43-53% agreed. When initial and follow-up requests were similar, compliance reached 76%.

The mechanism: Self-perception theory. Agreeing to a small request creates a self-image of "someone who helps this cause, " which people maintain through consistent behavior.

Application: If you want a major favor (introduction to a key investor), start with a small ask (feedback on your positioning). The initial "yes" creates momentum for larger requests.

4. Precision Signals Preparation Ambiguity creates cognitive load and triggers procrastination. Vague requests ("Can we grab coffee sometime?") require the recipient to do mental work. Specific requests ("Could we meet Thursday at 3 PM at Bluestone Lane for 30 minutes to discuss pricing strategy for B2B SaaS?") eliminate decision friction.

The mechanism: Research on negotiation demonstrates that precise numbers signal competence. Requesting $97,500 conveys analytical rigor. Requesting $100,000 suggests rough estimation.

Application: Replace "I'd love your advice" with "I need input on customer acquisition cost optimization for a two-sided marketplace—specifically whether to prioritize supply or demand in month one."

5. The Ben Franklin Effect: Asking Builds Relationships Jecker and Landy (1969) confirmed Benjamin Franklin's observation: people who do you a favor like you more afterward, not less. In their study, participants asked to return money to the researcher rated him 24% more likable than those who kept their money.

Franklin's original insight: "He that has once done you a kindness will be more ready to do you another, than he whom you yourself have obliged. "

The mechanism: Cognitive dissonance. When someone helps you, they rationalize the behavior: "I helped them, therefore I must like and value them. "

Application: Don't hoard favors. Asking for small favors early in a relationship actually strengthens it. Each ask that someone fulfills deepens their investment in your success.

The Cost of the Unasked Question Every avoided ask represents: 1.A skill not developed (asking becomes easier with practice)2.Information not gathered (even "no" provides data)3.A relationship not deepened (the Ben Franklin effect)A compounding opportunity foregone

The mathematics of compounding apply to networks and knowledge as much as capital. A single strategic introduction in year one can create partnerships, customers, and co-investors that reshape five-year trajectories. The professional who asks generates 48% more of these inflection points than the professional who waits to be noticed.

Every time you avoid asking, you're making a decision about what you deserve. You're saying implicitly that your needs matter less than someone else's convenience. That your company's survival is less important than avoiding a moment of discomfort. That preserving the illusion of self-sufficiency is worth the opportunity cost of the help you're not receiving.

Research by Davidai and Gilovich demonstrates that 76% of people's biggest life regrets concern inaction—things not done rather than mistakes made. Short-term, rejection stings. Long-term, unrealized potential haunts.

The Fortune of the Bold For the first thirty years of my life, I optimized for never needing help. The result: slower learning, smaller networks, years of unnecessary struggle. The moment I began asking—first with discomfort, then with systems—everything accelerated.

Five years later, I've asked for things I never thought I could. Introductions to investors who seemed unreachable. Advice from founders I admired. Strategic guidance when I was stuck. Asked Miss India on a date (she hasn't said yes yet). Raises that recognized my value. Favors from people I barely knew.

Roughly half said yes. Some became investors. Some became mentors. Some became friends. None of it would have happened if I'd waited for them to notice I needed help.

The difference between the founder who builds something meaningful and the founder who stays stuck isn't talent, capital, or timing. It's willingness to ask. To state clearly what you need. To give people the opportunity to help. To persist when the first answer is no.

Your brain will tell you asking is dangerous. Your childhood conditioning will tell you asking makes you needy. Your imposter syndrome will tell you that you don't deserve help.

The data says all of this is wrong.

As the Latin proverb states, Fortes fortuna adiuvat—fortune favors the bold. But fortune cannot favor you if you do not give it the opportunity.

Your next breakthrough exists on the other side of a question you haven't asked yet.

The Inheritance of Silence I understand why asking feels hard because I spent the first thirty years of my life operating on the wrong side of it.

I grew up in a family where asking for anything was quietly discouraged. It's not that my parents ever said "don't ask for help" —they simply never did. They worked constantly, solved every problem themselves, and wore their self-reliance like armor. Money was tight. Resources were scarce. And the unspoken message was clear: strong people handle their problems independently.

By the time I was building my first startup, this had crystallized into identity. My claim to fame was that I had never asked my parents for money. Not once. Even when I was eating one meal a day, stomach empty and head spinning. Even when I had a stroke at 29 from the stress and still didn't ask for help. Even when I had three months of cash in the bank to make payroll.

I had a list of twelve people who had explicitly offered to help "if I ever needed anything. " I contacted exactly zero of them. Because asking would mean I wasn't capable. It would expose me as someone who couldn't execute independently. It would burden people who had better things to do.

The real question though is: What was I protecting? My pride. An identity built on childhood conditioning that had no bearing on building a successful company. I was optimizing for the wrong variable entirely.

Where This Fear Comes From

Our reluctance to ask doesn't come from nowhere. It's installed—by childhood, culture, and early career conditioning.

Childhood Scripts Many of us grew up with "good kid" programming. Be polite. Don't make trouble. Don't ask for too much. Psychologists call this personalization bias. If you grew up hearing "Handle it yourself" or "Don't be a burden," you internalized a message: my needs are problems.

Research from the University of Leipzig demonstrates that children exposed to coercive communication—"stop bothering me, " "you should be able to handle this yourself, " "I'm busy" —develop significantly different emotional responses than those raised with assertive communication. The child internalizes: asking is bad. I am bad for needing things. This persists into adulthood as the belief that asking makes you weak, needy, or burdensome.Cultural Reinforcement In cultures like India and other collectivist societies, the script is even stronger: Don't stand out. Don't disrupt harmony. Don't ask for special treatment. Approximately 60% of people in collectivist cultures exhibit asking-aversion because standing out—even to get help—risks bringing shame to the family or group.

First-generation immigrant entrepreneurs from these backgrounds face particular tension: their cultural upbringing says "don't make waves, " while Western entrepreneurship demands aggressive self-promotion and explicit asks.Growing Up Responsible If you were the kid who managed household crises, calmed your parents' nerves, or took care of younger siblings, you learned to suppress your own needs. You learned that asking created more problems than it solved.

Hooper's research shows this kind of role-reversal—called parentification—leads to adults who chronically over-function, feel guilty when receiving help, and struggle to articulate their own needs.

This compounds for first-generation achievers. Studies show imposter syndrome affects 76% of first-generation college students. The internal narrative: "I already got lucky getting in—I don't want to prove I don't belong."

The result: the people who most need mentorship, support, and feedback are the least likely to request it.

Dismantling the Cage: Why "Strong People Don't Ask" Is a Lie

These scripts create the belief that strong people don't ask. But every piece of evidence points in the opposite direction.

Evidence 1: Asking Makes You Look Smarter, Not Weaker Brooks, Gino, and Schweitzer's study across thousands of professionals found that individuals who seek advice are perceived as more competent than those who don't. The effect is strongest when the task is difficult—asking for help on hard problems actually boosts competence perception.

Why? Because asking signals meta-cognitive awareness. It demonstrates that you understand the complexity of the challenge and possess the strategic intelligence to gather resources before acting. Observers don't think "they're incompetent. " They think "they're smart enough to know what they don't know.

Evidence 2: People Want to Help More Than You Think Vanessa Bohns' research across more than 14,000 strangers with various requests found that people underestimate compliance likelihood by up to 50%. People estimated needing to ask 7.2 strangers to get one to escort them to the gym. Actual number needed: only 2.3 people—meaning every other person said yes.

Even for uncomfortable requests like vandalizing a library book, more than 64% of people complied despite expressing reluctance.

The mechanism: help-seekers focus on the cost to the helper—the time, the effort, the inconvenience. What we systematically fail to appreciate is the social cost of saying "no. " Refusing triggers guilt, threatens self-image as a helpful person, and creates awkwardness that most people prefer to avoid.

Recalibrate your expectations. If you think you need to ask five people to get one "yes, " the actual number is closer to two. Your pessimism about compliance rates is not realism—it's systematic miscalibration.

Evidence 3: Helpers Feel Better Than You Expect Zhao and Epley (2022) found across 2,118 participants that help-seekers underestimated how positively helpers would feel when asked and overestimated how inconvenienced they would be. Being asked to help satisfies basic psychological needs for relatedness, autonomy, and competence.

When you ask someone for help, you're not burdening them—you're giving them an opportunity to feel useful and valued.

Evidence 4: Even Presidents Are Waiting to Be Asked Brian Chesky built Airbnb into an $80 billion company by systematically violating the assumptions most entrepreneurs accept about who you can ask for help.

When he wanted mentorship on community building, he asked himself: who is the most famous community organizer in the world? The answer was Barack Obama. Most founders would self-edit before typing the first sentence of that email, assuming a former President is categorically unreachable.

Chesky asked anyway. They established standing weekly one-hour calls. Obama gave him homework assignments. The relationship became one of the most valuable strategic assets in Airbnb's growth trajectory.

When Chesky asked Obama how many people he mentored, the answer was striking: "Hardly any." When he pressed for why, Obama's response demolished the core assumption that stops most people from asking: "Because no one asked me. "

This reveals a massive market inefficiency. High-status individuals are often under-utilized as mentors not because they lack availability or willingness, but because the market systematically assumes they are at capacity. The belief that "they are too busy" is a projection of the requester's insecurity, not a reflection of actual constraints.

The irony: busy, high-status individuals often prefer direct asks because they hate wasted time. A specific, well-structured request ("Could we discuss pricing strategy for two-sided marketplaces for 20 minutes on Thursday at 3 PM?") is easier to evaluate and respond to than vague relationship-building ("Let's grab coffee sometime").

Chesky's willingness to ask—to operate outside the boundaries most people accept—created asymmetric advantage. He accessed expertise, networks, and strategic guidance that competitors assumed was unavailable. The ask itself became competitive advantage.

The Principles of the Bold Request

Once we accept that the belief "strong people don't ask" is empirically false, we must operationalize the ask. Boldness is not just a mindset—it is a mechanical skill that can be optimized using behavioral science.

1. The "Because" Technique Increases Compliance 55% Ellen Langer's famous 1978 Harvard Xerox machine study found:1. Request only ("May I use the machine?"): 60% compliance2.Request + fake reason (" ...because I have to make copies"): 93% compliance3.Request + real reason (" ...because I'm in a rush"): 94% compliance

Simply including the word "because" followed by ANY explanation—even meaningless—increased compliance by 33 percentage points.

The mechanism: The human brain is wired for causal reasoning. Providing any explanation triggers a compliance script. The reason doesn't need to be compelling—it needs to exist.

Application: Never make a naked ask. Always include "because" followed by a reason: "I'm requesting 20 minutes because I'm facing a pricing decision in your domain and value your pattern recognition" vastly outperforms "Can we talk?"

2. "But You Are Free" Multiplies Compliance 4.75x Guéguen and Pascual (2000) found that adding "but you are free to accept or refuse" to a request for bus money increased compliance from 10% to 47.5%—a 375% increase. Meta-analysis of 52 studies (N=19,528) confirmed a medium effect size (g=0.44).

The mechanism: Acknowledging someone's freedom to decline paradoxically makes them more likely to accept. It removes psychological reactance—the instinctive resistance humans feel when autonomy is threatened.

Application: End requests with explicit acknowledgment of choice: "I would value your feedback on this deck, but you're completely free to decline if bandwidth doesn't permit. "

3. Small Requests Double Large-Request Compliance Freedman and Fraser's 1966 foot-in-the-door research found that without an initial request, only 22% of housewives agreed to let investigators enter their homes for 2 hours. With a brief questionnaire 3 days earlier, 43-53% agreed. When initial and follow-up requests were similar, compliance reached 76%.

The mechanism: Self-perception theory. Agreeing to a small request creates a self-image of "someone who helps this cause, " which people maintain through consistent behavior.

Application: If you want a major favor (introduction to a key investor), start with a small ask (feedback on your positioning). The initial "yes" creates momentum for larger requests.

4. Precision Signals Preparation Ambiguity creates cognitive load and triggers procrastination. Vague requests ("Can we grab coffee sometime?") require the recipient to do mental work. Specific requests ("Could we meet Thursday at 3 PM at Bluestone Lane for 30 minutes to discuss pricing strategy for B2B SaaS?") eliminate decision friction.

The mechanism: Research on negotiation demonstrates that precise numbers signal competence. Requesting $97,500 conveys analytical rigor. Requesting $100,000 suggests rough estimation.

Application: Replace "I'd love your advice" with "I need input on customer acquisition cost optimization for a two-sided marketplace—specifically whether to prioritize supply or demand in month one."

5. The Ben Franklin Effect: Asking Builds Relationships Jecker and Landy (1969) confirmed Benjamin Franklin's observation: people who do you a favor like you more afterward, not less. In their study, participants asked to return money to the researcher rated him 24% more likable than those who kept their money.

Franklin's original insight: "He that has once done you a kindness will be more ready to do you another, than he whom you yourself have obliged. "

The mechanism: Cognitive dissonance. When someone helps you, they rationalize the behavior: "I helped them, therefore I must like and value them. "

Application: Don't hoard favors. Asking for small favors early in a relationship actually strengthens it. Each ask that someone fulfills deepens their investment in your success.

The Cost of the Unasked Question Every avoided ask represents: 1.A skill not developed (asking becomes easier with practice)2.Information not gathered (even "no" provides data)3.A relationship not deepened (the Ben Franklin effect)A compounding opportunity foregone

The mathematics of compounding apply to networks and knowledge as much as capital. A single strategic introduction in year one can create partnerships, customers, and co-investors that reshape five-year trajectories. The professional who asks generates 48% more of these inflection points than the professional who waits to be noticed.

Every time you avoid asking, you're making a decision about what you deserve. You're saying implicitly that your needs matter less than someone else's convenience. That your company's survival is less important than avoiding a moment of discomfort. That preserving the illusion of self-sufficiency is worth the opportunity cost of the help you're not receiving.

Research by Davidai and Gilovich demonstrates that 76% of people's biggest life regrets concern inaction—things not done rather than mistakes made. Short-term, rejection stings. Long-term, unrealized potential haunts.

The Fortune of the Bold For the first thirty years of my life, I optimized for never needing help. The result: slower learning, smaller networks, years of unnecessary struggle. The moment I began asking—first with discomfort, then with systems—everything accelerated.

Five years later, I've asked for things I never thought I could. Introductions to investors who seemed unreachable. Advice from founders I admired. Strategic guidance when I was stuck. Asked Miss India on a date (she hasn't said yes yet). Raises that recognized my value. Favors from people I barely knew.

Roughly half said yes. Some became investors. Some became mentors. Some became friends. None of it would have happened if I'd waited for them to notice I needed help.

The difference between the founder who builds something meaningful and the founder who stays stuck isn't talent, capital, or timing. It's willingness to ask. To state clearly what you need. To give people the opportunity to help. To persist when the first answer is no.

Your brain will tell you asking is dangerous. Your childhood conditioning will tell you asking makes you needy. Your imposter syndrome will tell you that you don't deserve help.

The data says all of this is wrong.

As the Latin proverb states, Fortes fortuna adiuvat—fortune favors the bold. But fortune cannot favor you if you do not give it the opportunity.

Your next breakthrough exists on the other side of a question you haven't asked yet.

Heroes Ask for Help

Here is the single most damaging myth in professional life:

that asking for help is an admission of failure. We operate under the assumption that a bold request signals weakness, incompetence, or lack of preparedness.

The data shows the inverse is true.

Research from Harvard Business School and Wharton, led by Brooks, Gino, and Schweitzer, discovered a counterintuitive truth when studying thousands of professionals: people who asked for advice were rated as more competent than those who did not ask. Not slightly more. Significantly more. And the harder the problem, the smarter they looked for asking.

This article will show you why asking feels hard. What successful leaders do differently. And how to make the asks that change everything.

Resonating with this philosophy?

Join the smartest founders mastering the inner game to face the unknown. Read by YC & Sequoia.

To be continued…

A small favor...

I don't run ads. If this brought clarity, the biggest favor you can do is subscribe below.

.svg)

.svg)